Translational Medicine – From the lab bench to the patient’s bedside

Part 1: The Translational Chasms

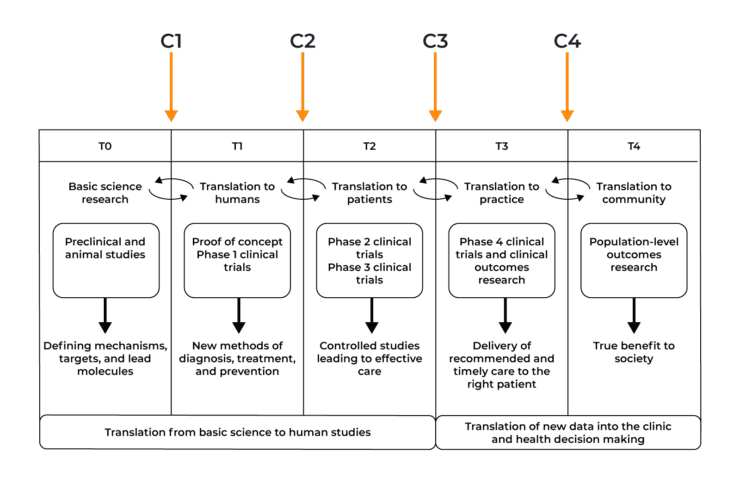

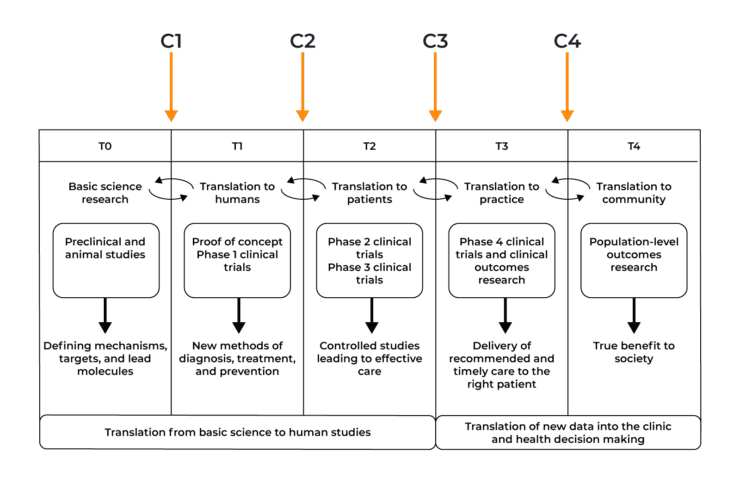

In order to maximise the number of novel and efficacious treatments available for patients at their ‘bedside’, several translational models have been created to visualise and streamline the process of getting drugs into a clinical setting.

The diagram below shows the operational phases of the translational model and the chasms between them. T0-T4 shows the translational phases required for drug development, C1-C4 shows the chasms between the phases that need to be overcome for successful drug approval.

1. Translational Chasm 1 (C1) in drug development T-0 (Basic Science Research) to T-1 (Translation to Humans)

In order for this first chasm to be crossed, the basic science discoveries uncovered in the lab environment must first have the potential to have a useful application. Many basic science discoveries help to form a clearer picture of how diseases work but may not have a direct application in terms of translation into the clinic. If a compound is deemed a suitable candidate it must undergo in vitro studies (testing in a test tube, culture dish, or elsewhere outside a living organism) and in vivo studies (in a living organism) studies to begin bridging the C1 gap into a proposed human application.

Arguably the biggest obstacle to be overcome in the first translational chasm is the lack of communication between different parties of the ‘translational continuum’. A researcher’s primary motivation is to uncover novel treatment targets whilst a pharmaceutical company must take into account both patient care and the financial burden of clinical trials. These different groups belong to diverse bodies, follow separate implicit or explicit rules, and respond to different sets of motivations or implementation criteria. Clinician scientists are rarely involved in the basic science experiments and are unable to uncover novel targets themselves. There is a clear need for both parties to unite with each other and improve the communication gap in order to optimise the T-0 to T-1 translation.

As a result of this gap, many candidates fall by the wayside at this point. Companies have more than likely already invested heavily before they get to human studies. Only promising candidates get taken to the next step and only after successful ‘bench’ data becomes available. This is a very costly aspect for companies as there are specific data sets required to ensure the regulators accept moving to human trials. It’s hugely important that companies invest in a strong regulatory strategy (an aspect CROs can help with) to support their drug development programme.

2. Translational Chasm 2 (C2) in drug development T-1 (Translation to Humans) to T-2 (Translation to Patients)

Once in vitro and in vivo work have undergone successful completion, the transition from animal tests to testing the effects on patients can begin. In order for a drug to become available for public use and deemed ‘safe’, it must undertake three phases of clinical trials:

- Phase 1 – Safety of pharmaceutical drug

A small cohort of typically healthy volunteers will be given the drug in varying doses to determine its safety profile. The general aim of a phase 1 clinical trial is to determine the maximum tolerated dose before toxicity.

- Phase 2 – Efficacy of pharmaceutical drugs

This phase uses a larger population of volunteers who typically have the disease the drug aims to treat. This allows for the testing of the drugs efficacy and safety profile further.

- Phase 3 – Clinical benefit of pharmaceutical drugs

The final phase involves randomised, double-blinded testing in a very large cohort of volunteers. Due to their high numbers, phase 3 trials allow for the monitoring of patient diversity of drug responses. This allows for the identification of the range of possible side effects or adverse reactions.

- Once a drug has received a Marketing Authorisation (MA) it can enter post marketing surveillance (also known as phase 4). This is a much longer phase than the previous three and can take several years due to the study of the drug’s long-term effects and its comparison to existing treatments.

Typically the second translational chasm stems from poor clinical trial design. As clinical study design improves, the risk of various trial biases have been decreasing, leading to more promising and accurate results.

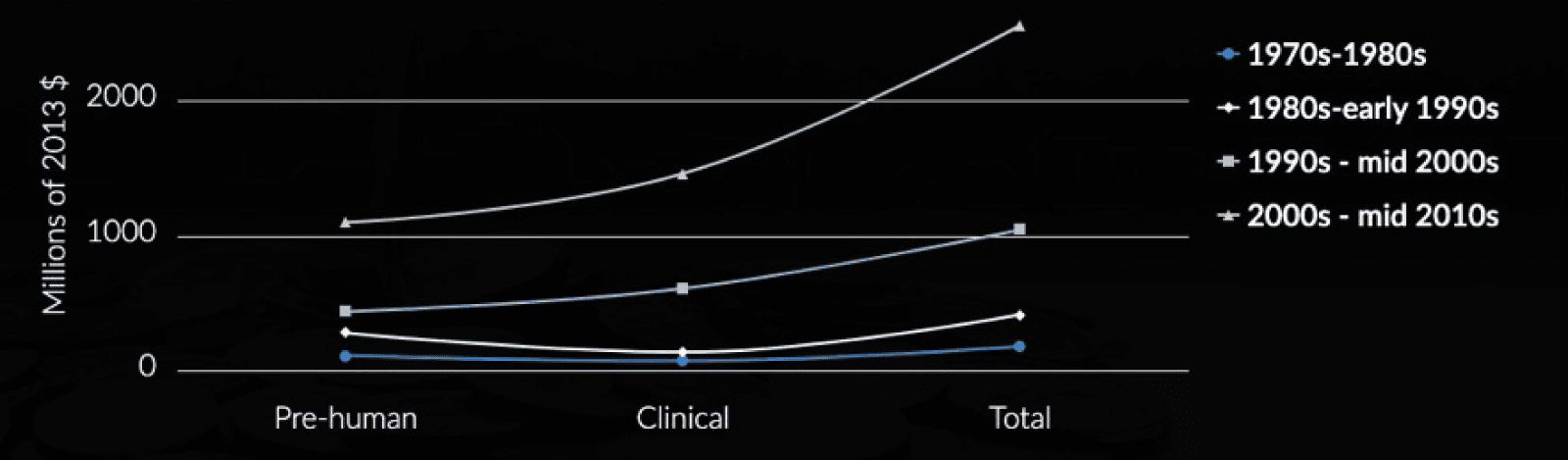

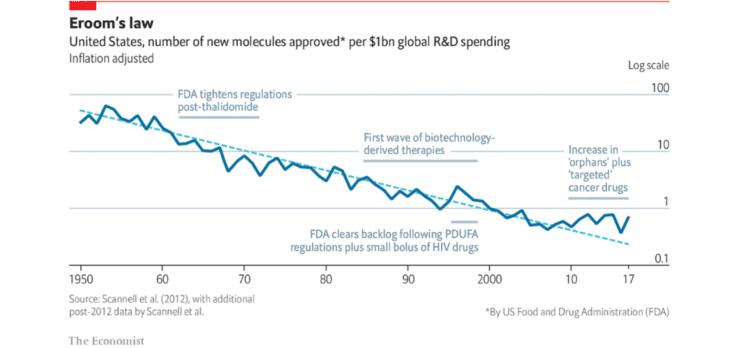

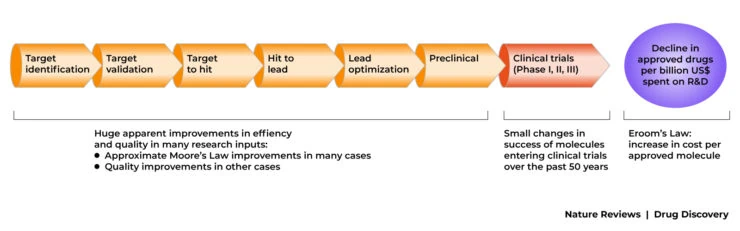

Further problems with the second chasm involve the poor success rate of drugs making it into the clinic. It can cost billions for pharmaceutical companies to discover, develop, test and seek the eventual drug approval by the relevant health authority.

The translation from T0-T3 is also highly inefficient with typically thousands of potential drug molecules being cut down to one successful compound. This chasm is being tackled by new clinical trial designs hoping to improve the translation from animal to clinical application.

Before even reaching this Translational Chasm, some biotech companies fail to get past the in vitro/in vivo stage as they cannot raise enough funds to progress. This, coupled with the financial implication of the C2 chasm can be a particularly expensive endeavour.

Inadequate trial design and a regulatory strategy that hasn’t been thought through properly can add to the high cost of clinical trials.

3. Translational Chasm 3 (C3) in drug development T-2 (Translation to Patients) to T-3 (Translation to Practice)

The third translational chasm involves the transition of a successful drug from its trial phases into routine clinical practice. This is typically initiated by the drug becoming licensed before implementation into standard practice.

The major flaw present in the third chasm comprises the poor implementation of clinical evidence. Many approved drugs can be used to treat several diseases other than the initial disease they aimed to treat, however this does not tend to come to light until the publishing of post marketing epidemiological studies. An example of this is the BCG vaccine (originally used to prevent the contraction of Tuberculosis) proving to be an effective treatment for bladder cancer.

A second example is the re birth of Thalidomide (a drug to treat morning sickness but was recalled due to teratogenicity) which has shown to be an effective treatment for skin and blood cancers. CROs play a critical role at this point, helping to deliver studies with new indications, bioequivalence studies, biosimilar studies in the most cost-efficient way. As a result of this chasm, clinicians are often unaware of the fact that such evidence can be generated and may not prescribe the most effective treatments for a particular disease until this has been proven in a clinical trial.

One of the costliest aspects of the C3 chasm is primarily the cost of the drugs themselves.

A novel compound or drug that has been granted marketing authorisation is usually patented by the Sponsor who ran the clinical trials. For a period, these drugs can be charged at a premium for the Sponsor to recover the cost of drug development and to generate a profit, however over time, bioequivalence studies, cheaper manufacturing methods and the expiry of drug patents can lead to the creation of generic drugs. CROs often run many of the different trials required for Sponsors to retain patent longevity by changing the drug indications in different demographics, re-formulation to improve them, or change drug delivery methods for faster absorption or ease of administration.

4. Translational Chasm 4 (C4) in drug development T-3 (Translation to Practice) to T-4 (Translation to Community)

The final translational chasm sits between an approved drug and its acceptance into the public healthcare system. C4 takes a step back and takes a look at the overview of a drug’s impact on healthcare as a whole. Research into wider outcomes include public health surveillance of disease incidence, morbidity and mortality, and health-related quality of life indicators in populations defined by geographic and demographic categories.

When looking at disease treatments, one of the most common reasons for falling into the fourth chasm is its cost. This is particularly evident when looking at some immunotherapeutic therapies, which can cost in excess of £100,000 per year per patient with little increased benefit compared to existing, cheaper treatments.

Bioinformatics may play a larger role in minimising the size of this final chasm as the processing of big data sets is allowing for better health surveillance. Population studies, coupled with an increased investment from governments can ease the transition of drugs into the public health sphere.

It is imperative companies are aware of the current market status and healthcare requirements when designing their studies. Health economic data and patient reported outcome measures are key to this and are fundamental to overcoming the C4 translational chasm. A regional CRO can assist Sponsors in this area.

Summary on chasms in drug development

It is important to note that the translational continuum is not necessarily chronologically linear as shown earlier. Aspects of each operational phase can feed into each other both forwards and backwards. For instance, public epidemiological examination in T-4 may help to inform the need to look at a specific subset of drug targets in T-0. This is known as the reverse translational medicine axis– from bedside to bench.

It’s the feedback loops between operational phases that make translational medicine so effective. In the coming years, the various groups that make up the translational continuum should continue to work on improving their cohesion and overcoming their respective translational chasms.

Effective translational medicine should build upon the three pillars of bench, bedside and community with the discovery of new, novel compounds by basic scientists, the implementation of these compounds by pharmaceutical companies/clinicians and the impact these drugs have by public healthcare authorities.

Due to the four key translational chasms, drug development can be an expensive endeavour. C1 expense relies on successful ‘bench’ data with a strong regulatory strategy and financial backing to push it through to its T-1 stage. C2 costs are also impacted by inefficient regulatory strategies coupled with incorrect investment priorities and poor trial design. C3 financials are affected by the market itself, Sponsor competition, clinical development timelines and a constantly changing healthcare landscape. C4 cost implications become transparent if the final community pillar is not afforded proper due diligence. Without constant patient driven feedback, Sponsors would not be able to effectively improve their products or inform on future directions for their pipeline.